I arrived in Stockholm after a seven-hour train ride from Oslo, Norway, that took me across parched and flat farmlands. At Stockholm central, I sprinted to the closest kardemummabullar seller (cardamom roll) that I could find. Once satiated with this sweet and spice-filled delight, I navigated the mass transit system to the island of Skeppsholmen, my home for the night. I stayed in a repurposed wooden ship in a room with five roommates and two tiny portholes.

The dreamy kardemummabullar.

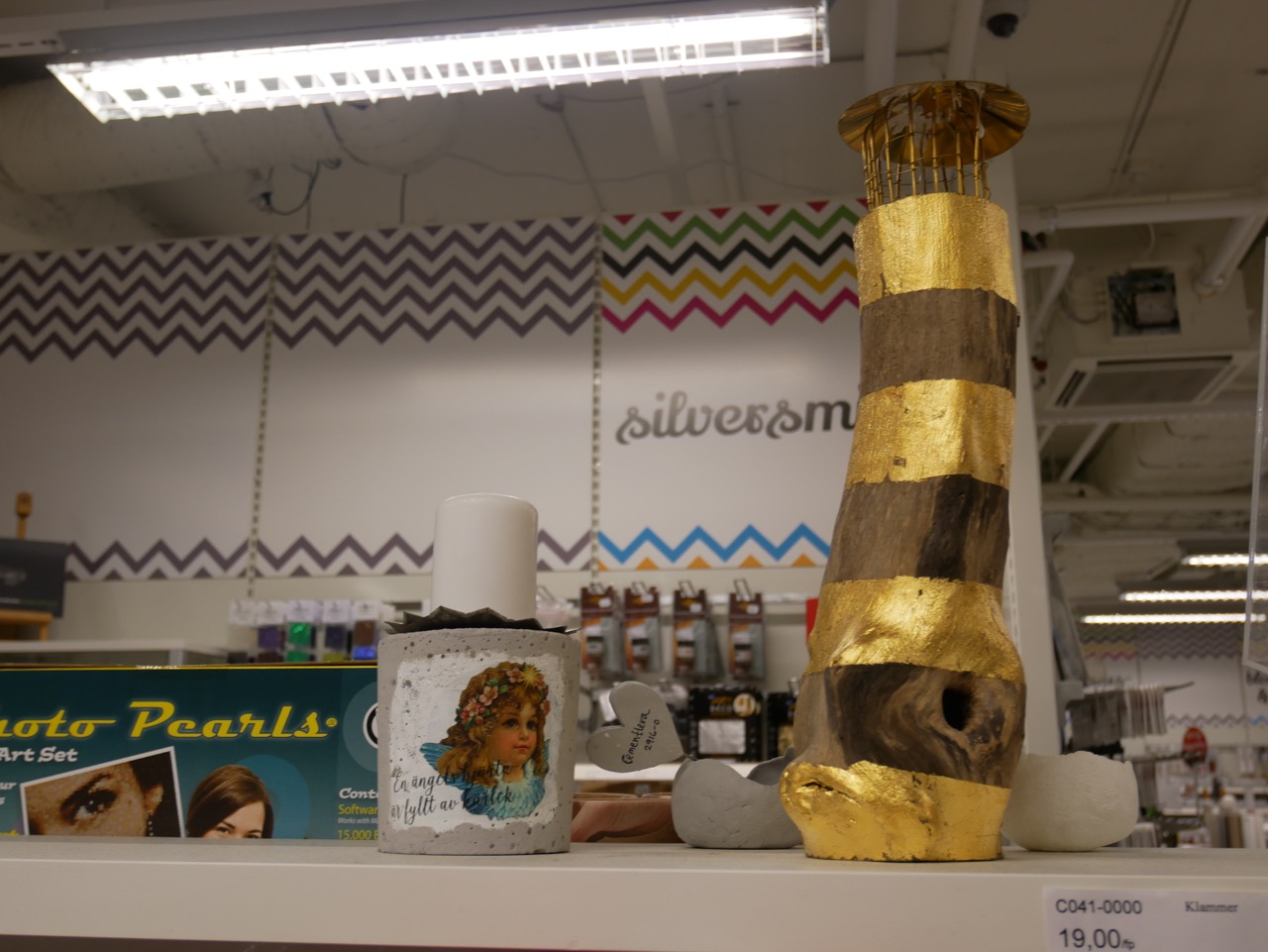

High quality selection of tools at the arts and crafts store.

Funky gold leaf project on display at Slöjd Detaljer.

I hadn’t treated myself to a restaurant in a month of travels, so decided to put my highly advanced Swedish language skills to use and find me some köttbullar (meatballs). I read reviews on Yelp of the best meatballs, (probably according to American visitors) and found a place close to my hostel.

When I walked in, the historic wooden interior, stained glass ceiling and wine glass-holding clientele suggested that my sweatpant culottes and bulging day backpack were a little out of place. The waitress came to my table and said in English, “Let me guess, you want the meatballs?” to which I proudly and slowly replied, “No. Jag vill skulle köttbullar och potatismos.” (No. I would like meatballs and mashed potatoes.”) Fortunately she smiled and complimented my pronunciation of “köttbullar” which is surprisingly “shet-boolar” (Tack to my language teacher, Rose Arrowsmith DeCoux.)

While devouring the classic Norwegian novel, Hunger, by Knut Hamsun (1890), I ate the salty gravy-covered meatballs, mashed potatis and tart lingonberry jam.

#potatis #köttbullar

I watched a dramatic sunset through the porthole that night and slept well on the lightly rocking ship.

The next morning I put my tourist game face on, woke up early, and hopped on a ferry to Scandinavia’s most popular museum, the Vasa Museum, which is home to a monumental 17th century warship.

I decided to release my pent up energy by dancing to the museum, in the style of early ipod advertisements – white earbuds and a tiny screen in my hands.

What I looked like dancing in Stockholm.

Because it was so early, few folks were around so I let loose and imagined I was my dance hero Anne Marsen from the amazing Girl Talk music video “All Aboard.”

My dancepiration & doppleganger, Anne Marsen.

Once I got in to the museum, I was in instant awe of the ship’s jaw-dropping scale.

The bow of Vasa. It felt impossible to take a single photo of the entire ship.

I consider it the ultimate bestest museum of hubris. It is home to a 226’ long wooden warship that was sunk by a sudden breeze, 25 minutes into its maiden voyage in 1628. The design was top heavy due to its two decks holding 64 cannons and a narrow beam (width) at 38’. But like so many things in life, something that initially was, “oh no, that’s bad...” became, “oh no, that’s good!”

Because it sank so quickly, it was in relatively shallow water and was able to be excavated and restored starting in the 1960s. It’s the largest intact shipwreck in the world and the most visited museum in Scandinavia. It’s also a really inspiring and didactic museum model with thorough displays, conservationists you can talk to and an amazing building design with artificial masts on the top of the roof.

Onsite conversational conservationists.

I particularly enjoyed seeing the ornate figure carvings, with Roman emperors, the king’s son, an enormous lion and much more.

The ornate stern of the ship. Description from the exhibit: "The national coat of arms, Sweden's symbol. The lions have featured since the 13th century. The three crowns symbolize the Three Holy Kings. The central shield bears the arms of the Vasa family, a sheaf of corn, ("vase" in old Swedish). The crown emphasizes the royal status of the dynasty."

Description from the exhibit: "Two griffins - Charles IX's heraldic animals - hold the royal crown above the young Gustavus Adolphus' head. As a boy he was already his father's chosen successor."

An approximation of what some of the ship's carvings would have looked like with their original colors.

An exterior room connected to the captain's quarters.

Close up of carved figures from the roof of the exterior room.

Lion at the bow of the ship.

After viewing the ship, I hopped on a ship, and went back to my ship.