When I walked into the classroom and counted five Japanese sharpening stones in the kitchen sink, I knew I was in the right place.

Japanese water stones for sharpening.

It was Wood Week at North House Folk School, and two Japanese woodworkers had traveled all the way to northern Minnesota to share their knowledge. I drove from coastal Maine, past the finger lakes and four great lakes, to make it to this special event.

Shinichi Moriguchi, a master tray carver, and Masashi Kutsuwa, a professor and green woodworker at Gifu Academy of Forest Science and Culture, traveled together and gave presentations on Japanese tool use, woodworking and craft history.

Shinichi Moriguchi demonstrating how to use mini wedges to split the wood into tray blanks.

One of the main workshops was about Wagata-bon tray carving, and was taught by Shinichi Moriguchi and Masashi Kutsuwa. “Wagata” refers to the small village of Wagatani, in Ishikawa-ken, and “bon” means tray. It’s a small miracle that this craft tradition is still alive and well.

L>R: Eager learner Rose Holdorf, Shinichi Moriguchi, and Masashi Kutsuwa, explaining the natural dye made of steel wool, chesnut wood and water, used to stain the wagata-bons. For a quick video, go here.

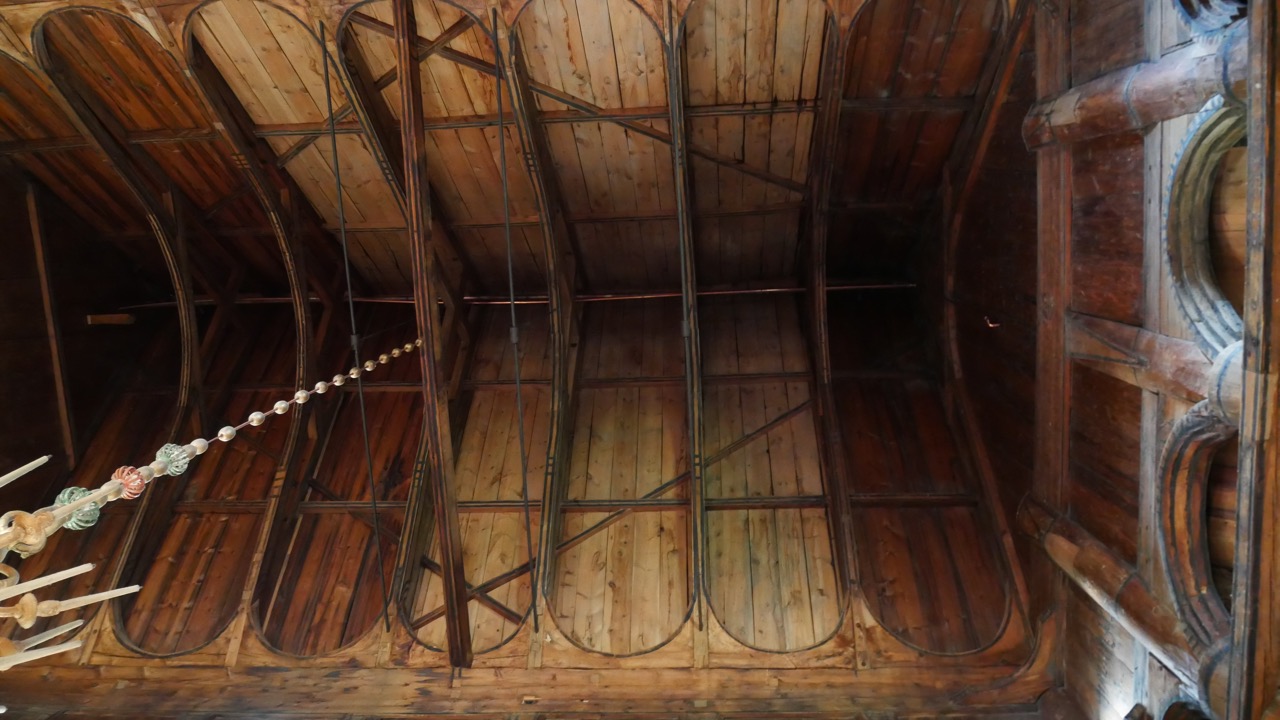

Wagata-bon were originally made by wooden roof shingle makers in the small village of Wagatani. They would set aside some of their best shingle blanks, and carve them into trays during the winter, to use as a barter item for clothing and food. They were often made of chestnut wood, which splits well and has a high amount of rot-resistant tannins.

Wagatani’s local Hachiman shrine. Note the hanging sign with gold kanji above the entrance is a wagata-bon.

A close up of the wagata-bon sign above the Hachinman shrine entrance in Wagatani.

If you look closely, you can see the wooden shingle roofs in Yamanaka, a town 3 miles downstream of Wagatani. Taken at some point between 1920 - 1931.

Unfortunately the tradition was almost entirely lost when the town of Wagatani was flooded by the construction of a hydroelectric dam in the early 1960s. People were forced to abandon the village, and left behind some of their possessions to lighten their load. Apparently when the water flooded the village, some wagata-bon trays floated to the surface.

This was not the only evidence left behind of the tradition. After the announcement of the dam’s construction but before the town was flooded, renowned woodworker and lacquerware finisher Tatsuaki Kuroda (1904-82) wrote an article for the craft publication Mingei Techō in 1963 to highlight wagata-bons. He saw them as a prime example of Japanese mingei, or folk craft. It’s an item made for everyday use, by everyday folks, by hand and often unsigned. Kuroda was contemporaries with Yanagi Soetsu (1889 – 1961), who is the founder of the Japanese mingei movement, and author of The Unknown Craftsman, an influential work on the philosophy of Japanese folk craft. Kuroda’s article helped to raise awareness about this almost extinct tradition.

A few examples of wagata-bon. Source: Bulletin of The Ishikawa-ken History Museum (2005).

Our teacher at North House, Moriguchi, actually heard about wagata-bons through a connection he had to Tatsuaki Kuroda. Moriguchi studied art and design at an art university, and afterwards studied fine furniture making and lacquer finishing from Kenkichi Kuroda, the son of Tatsuaki Kuroda. Moriguchi first heard about the trays from Kenkichi’s wife, who mentioned that his work resembled wagata-bon. After learning about these trays, Moriguchi ‘swerved’ (shout out to Michelle Obama’s Becoming), and decided to move away from fine furniture making and instead dedicate himself to traditional wagata-bon tray carving.

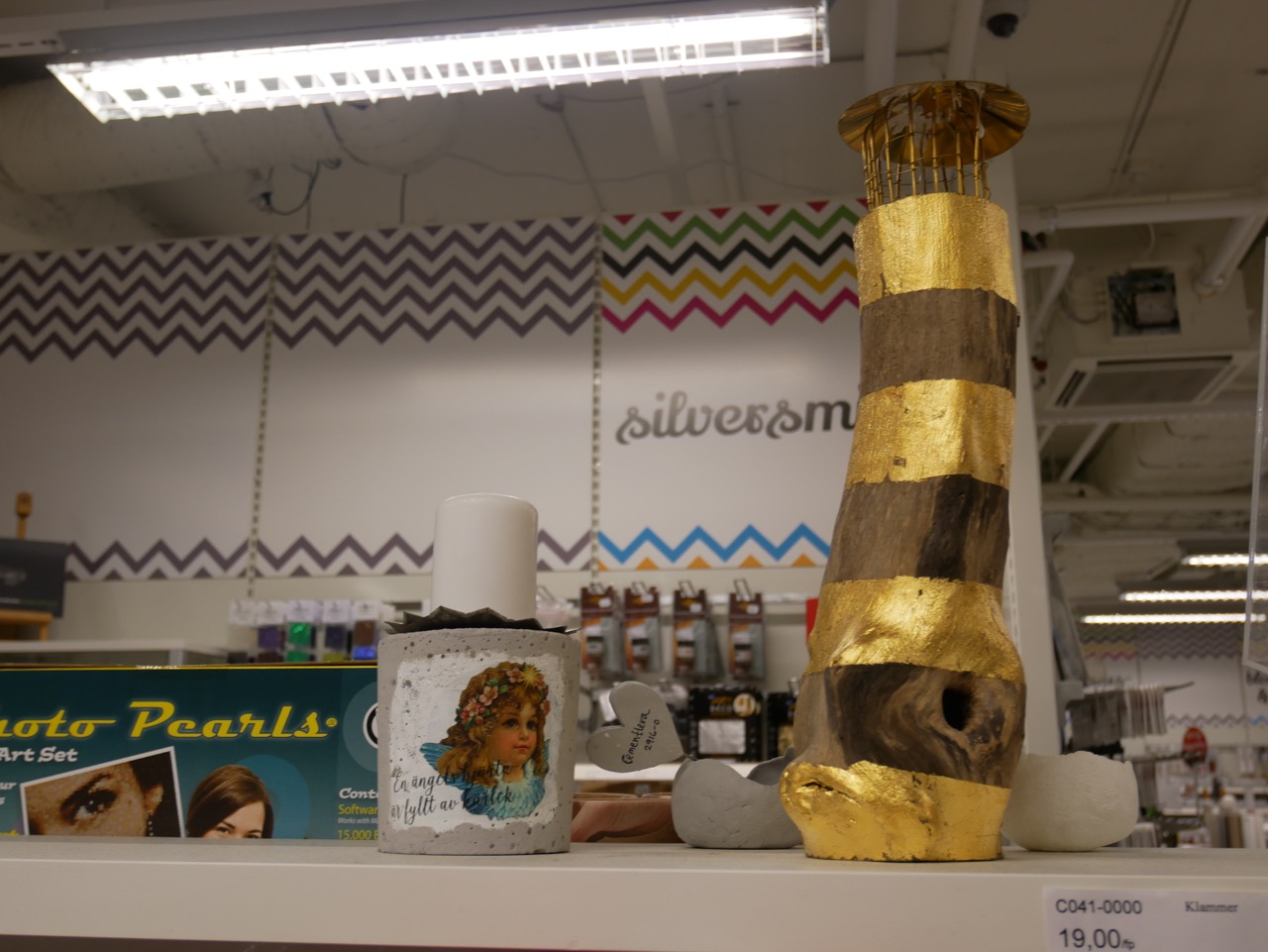

Moriguchi’s wagata-bons - most are finished with a chestnut and steel wool stain and then smoked.

Moriguchi is not only a committed craftsperson but also a committed teacher. Traditionally in Japan crafts are passed from master to apprentice, through a grueling apprenticeship which can last many years and involve almost no direct instruction. However Moriguchi eagerly shares his knowledge and encourages people to develop their own style. He even rents an abandoned building near the former village of Wagatani, and teaches free workshops to local people. He also travels throughout Japan to teach, and this was his first time teaching wagata-bon carving in the U.S. It was amazing that our paths were able to cross in northern Minnesota and I intend to teach this skill to others as well so it can continue to live on.

Lifelong learners (& teachers) Rose Holdorf & Liesl Chatman carving away.

Students’ wagata-bons at the end of the workshop.

Making my second wagata-bon in the workshop. Silver maple. Mora caring knife fan T-shirt and Japanese tenugui (bandana) from Otsuchi, Iwate-ken.

Thank you to Masashi Kutsuwa for sharing great resources on this topic!